Letter 34

precedent in the history of the Church in both its innovative

content and in the room it left to the celebrant’s personal initiative.

It immediately aroused attitudes of reticence and resistance,

from the highest levels of the Church --Cardinals Ottaviani and Bacci

communicated their intervention to Paul VI a few weeks before the new

Missal was to become normative-- and from simple laymen. It also provoked

a reaction on the part of many personalities in the artistic, literary, and

scientific worlds. They were worried by the cultural step backwards

the reform represented and they expressed their concern in the Times on

6 July 1971; this was the origin of the so-called “Agatha Christie” indult.

In point of fact, by the time Paul VI passed away barely ten years later, it was

already clear--even to its promoters--that this reform had not met its goals and

had even begun to empty out the churches.

And so at the beginning of the 1980s a common-sense reaction manifested itself

more and more clearly: why not leave the older liturgical forms available to those

who found their sacramental spiritual nourishment in them? Since everything now

seemed to be free and allowed, why not also freely allow what had been done before?

After all, hadn’t Paul VI himself made a strong and meaningful gesture by relegating

Archbishop Bugnini, author of the reform, to Tehran? Hadn’t the Pope understood that

the Mass that was forever to bear his name and which was intended to be a brightly

shining sign of the conciliar springtime turned out to be a ferment of division

in an ever-weakening Church?

As soon has John Paul II’s papacy began, the question of freedom for

the pre-conciliar Mass emerged. Although it took thirty years for it to

find an answer in Benedict XVI’s Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum,

it had in fact been foreshadowed at the time by the two personalities

who were to go down in history as the key figures in the solution to the

liturgical fracture, namely Joseph Ratzinger and Marcel Lefebvre--

like it or not and whatever judgment one may have regarding one or

the other of them.

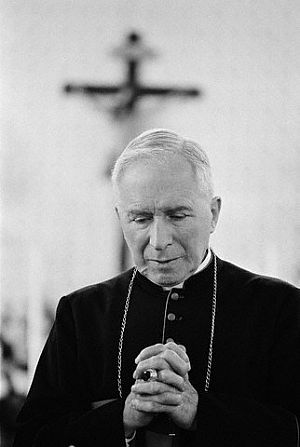

I – ARCHBP LEFEBVRE: A 1979 “PROPHECY” ABOUT THE FREEDOM OF THE MASS

On 11 May 1979, Archbp. Lefebvre made the following declaration to his seminarians

at Écône:

“If in fact the Pope gives the traditional Mass a place of honor in the Church,

well then you know, I think we’ll be able to say that the essential part of our victory

has been won. The day when the Mass truly becomes the Church’s Mass once again,

the Mass in parishes, the Mass in the churches--oh, there’ll still be difficulties,

there’ll still be quarrels, there’ll still be oppositions, there’ll still be all sorts of things

--but still, the Mass of all time, the Mass that is the heart of the Church, the Mass

that is the essential thing in the Church, that Mass will take its place back,

perhaps it won’t have enough place yet, obviously it will need to be given an even

greater place yet, but still and all, the very fact that every priest who wants to

will be able to say that Mass, well I think that it would have enormous consequences

in the Church.

I believe that we would have been of service for such a time, if truly it ever came

to pass . . . . Well, for my part, I believe that the Tradition is safe. The day when

the Mass is saved, the Church’s Tradition is safe, because along with the Mass

there are the sacraments, along with the Mass there’s the catechism,

along with the Mass there’s the Bible, and all the rest of it . . . . After all,

the seminaries and the Tradition would be saved. I believe that one could then almost

say that one saw morning dawning in the Church; we’d have made it through

a mighty storm, we’d have been in complete darkness, beaten by every wind

and every tornado, yet still at last there on the horizon the Mass had risen again,

the Mass that is the Church’s sun, our life’s sun, the sun of every Christian’s life . . . .”

(source: Credidimus Caritati website)

“The very fact that every priest who wants to will be able to say that Mass,

well I think that it would have enormous consequences in the Church”:

is this not precisely the fundamental contribution of the 2007 Motu Proprio?

The SSPX greatly rejoiced over this liberating text through Bishop Fellay’s statements

--which was only fair since its founder had announced it as a

“morning dawning in the Church”!

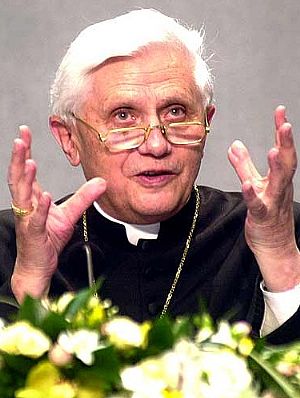

II – CARDINAL RATZINGER: THE PRINCIPLE OF FREEDOM OF THE MASS LAID DOWN IN 1982

This liturgical freedom was in the air at the beginning of John Paul II’s pontificate.

It is now known that as soon as he had been named Prefect of the

Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (and unofficially put in charge

of the file on liturgical disputes by Pope John Paul II), Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger

was organizing a meeting on 16 November 1982 at the Palazzo del Sant’Uffizio

“regarding liturgical questions”(1), namely regarding both the liturgical problem

as such and the problem of the SSPX.

1982. Exactly a quarter of a century before Summorum Pontificum, therefore.

During this meeting, Cardinal Ratzinger had obtained that every participant

without exception (2) state as common-sense evidence that,

“independently from the ‘Lefebvre issue’, the Roman Missal in the form it had until

1969 must be allowed in the whole Church for Masses celebrated in the Latin language.”

The prelates in attendance had also spoken about the question that was related to the

liturgical question, namely the question of the SSPX, and deemed that its resolution

ought to begin with a canonical visit (which in fact occurred five years later).

III – LEFEBVRE/RATZINGER: A SHARED VISION FOR THE SPREAD OF LITURGICAL FREEDOM

This liberation process of the unreformed liturgy--a process as incredible as

the Bugnini reform itself--has progressed in specific steps throughout the

quarter century since Cardinal Ratzinger made his stance known.

In practice, this process turns out to be closely linked to the canonical

settlement of questions concerning the SSPX, even though everyone

officially maintains that these are two distinct issues.

a) On 18 March 1984, Secretary of State Cardinal Casaroli, at the request

of Cardinal Ratzinger, writes to Cardinal Casoria, Prefect of the

Congregation for Divine Worship, to ask him to prepare the first act restoring

the use of the traditional missal: “Absolutely forbidding the use of the above

mentioned Missal can be justified neither theologically nor juridically.”

On 3 October 1984, Cardinal Casoria’s successor at Divine Worship,

Bishop Mayer, therefore addressed to the presidents of episcopal conferences

worldwide the circular letter Quattuor abhinc annos, the so-called “1984 indult”

authorizing celebration according to the 1962 Missal “for the benefit of those

groups that request it.”

b) On 30 October 1987, the last day of the Synod on the laity’s

“Vocation and Mission in the Church and in the World,”

Cardinal Ratzinger announces to the bishops that an Apostolic Visitor

has been appointed to Marcel Lefebvre’s work: the Canadian Cardinal Édouard Gagnon,

president of the Council for the Family. After this visit, which took place in April

and May 1988, came the negotiations between Cardinal Ratzinger and

Archbp. Lefebvre. These resulted in the 5 May agreement that Archbp. Lefebvre

would eventually denounce--basically because of its lack of guarantees

regarding the nomination and consecration date of another bishop for the Society.

Indeed Archbp. Lefebvre then goes ahead with the consecration of four bishops

at Écône on 30 June 1988.

Rome, in reaction to this act, publishes the Motu Proprio “Ecclesia Dei”

on 2 July 1988. While condemning Archbp. Lefebvre, it institutes a Pontifical

Commission for “the purpose of facilitating full ecclesial communion of priests,

seminarians, religious communities or individuals” attached to the 1962 Missal

and to oversee the bishops’ implementation of the 1984 indult.

c) In January 2002, the failed 1988 agreement between Archbp. Lefebvre and

Rome is made in favor of Bishop Licinio Rangel, successor to Bishop de Castro Meyer,

the head of the traditional community of the Campos diocese. A personal ordinariate

is created and, in June of the same year, Rome accepts for a coadjutor to be

designated to succeed to Bishop Rangel automatically. A community numbering

over 20,000 laymen, about twenty priests, and as many schools thereby

returns to full communion with Rome while fully retaining its preconciliar liturgical uses.

d) On 7 July 2007, to crown this process, Pope Benedict XVI promulgates the

Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, which restores to every priest the private use

of the 1962 Missal and invites pastors to give a favorable answer to stable groups

of the faithful who wish to benefit from it.

This text, which the superior of the SSPX hailed, is an “universal Church law”

(Universæ Ecclesiæ instruction) and promotes contacts between Rome and Écône.

It will also prepare the ground for January 2009, when the excommunications of the

bishops who had been consecrated in 1988 were lifted.

IV – LITURGICAL LIBERTY / THEOLOGICAL LIBERTY: JOSEPH RATZINGER’S JULY 1988 SPEECH ON ARCHBP LEFEBVRE

In our French 4 June 2010 Letter (PL 233) on Mgr. Brunero Gherardini book,

The Ecumenical Council Vatican II: A Much Needed Discussion

(Casa Mariana Editrice, 2009), we mentioned a very significant speech

that Cardinal Ratzinger had given on 13 July 1988 before the bishops of

Chile and Colombia (3). In that allocution, the future pope examined the

responsibilities of all and sundry in the light of the episcopal consecrations

that had taken place at the hands of Archbp. Lefebvre at Écône on 30 June 1988.

Now this speech includes two statements that are essential for a proper understanding

of the current pontificate:

a) “The truth is that this particular Council defined no dogma at all, and deliberately

chose to remain on a more modest level, as a merely pastoral council; and yet many treat

it as though it had made itself into a sort of superdogma which takes away the

importance of all the rest.”

b) “It is a necessary task to defend the Second Vatican Council against Archbp.

Lefebvre, as valid, and as binding upon the Church.”

Hence an as yet unresolved difficulty that has been weighing on the recent

discussion between the SSPX and Rome: how “binding” on the faith can teachings

be that were expressed “on a more modest level” than that of the Creed?

This parallel may sound shocking to some: why not apply to the Council what

the Holy Father applied to the liturgy? In order to relativize the new Mass’s

character as a “super liturgy”, the Pope, in the MP Summorum Pontificum, recalled

that the older Mass had never been forbidden and he gave its free use

(in theory at least) back to priests and the faithful.

V – THE REFLEXIONS OF PAIX LITURGIQUE

1) The declaration that Archbp. Lefebvre made on 11 May 1979 is surprising

not only because of its early date but also because it sets the Écône prelate

in a light different to that which is usually applied to him. Nothing is vehemently

polemical or rigid or even ‘sectarian’ in these 1979 words. They express a hope

concerning the Church’s concrete life. This is “pastoral Lefebvre” in the sense

given to the term during the Council, but with a different content: that

of an intraecclesial ecumenism with a concrete experiment of freedom for

the traditional Mass at the parish level with a view to fostering liturgical,

spiritual, and doctrinal renewal.

The founder of the SSPX expresses his hope to see the traditional Mass freely become

“the Mass in parishes, the Mass in the churches.” Of course, he grants that

“there’ll still be difficulties, there’ll still be quarrels, there’ll still be oppositions,

there’ll still be all sorts of things.” But he goes straight to brass tacks

in a very concrete manner: “that Mass will take its place back, perhaps it

won’t have enough place yet.” He thus assigns a set goal to his work,

especially since it seems so modest: “The very fact that every priest

who wants to will be able to say that Mass, well I think that it

would have enormous consequences in the Church. I believe that that

we would have been of service for such a time, if truly it ever came to pass.”

Archbp. Lefebvre then develops the theme of the coherence between liturgy

and doctrine: “along with the Mass there are the sacraments, along with the Mass

there’s the catechism, along with the Mass there’s the Bible, and all the rest of it . . . .”

2) As for the process of liberation that Cardinal Ratzinger initiated in 1982,

it is just a pastoral and concrete. One may speak of an “homogenous evolution,”

just as in the case of dogma, except here applied to the practical liberalization of

the Mass that is now called extraordinary:

-Quattuor Abhinc Annos circular letter, 3 October 1984: the traditional Mass

may be authorized by the bishops, but under certain conditions and not in parish churches;

- Motu Proprio Ecclesia Dei Adflicta on 2 July 1988: bishops are invited to allow

it more widely and more generously in their dioceses (in theory);

- erection of the Saint-Jean-Marie-Vianney Personal Apostolic Administration in

Campos, January 2002: it may be the only source for a large community’s Eucharistic life;

- Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, 7 July 2007: the decision is now up to the pastors

for their own parishes (in theory); most importantly this Mass is declared never to

have been abolished and its private celebration becomes a right for every

Roman rite priest, without restriction;

- logically, a text will eventually come out acknowledging pure and simple freedom,

a “normal” freedom as Cardinal Cañizares put it, to celebrate the extraordinary Mass

in every church. The “Mass of all ages” would then become the “Mass of all places”

for the Roman rite.

3) The hurdle that needs to be overcome for this last step is the fact that

there was a move from the non-dogma of Vatican II to a “superdogma”,

which also applies to the liturgy of Vatican II; there was a move from a

non-infallible council that does not engage the faith to a tyrannical

so-called “Spirit of the Council,” which seeks also to dogmatize the new

forms of divine worship.

All in all, what needs to be defended is a healthy freedom, a true

theological freedom, not to question Catholic dogma but to explain

it and even to help it “progress”--i.e. to advance its proper understanding.

This freedom is closely intertwined with a healthy liturgical freedom, not a freedom

for all sorts of abuse, but a freedom to illustrate, defend, and advance the

faithful’s faith in Eucharistic transubstantiation, their faith in the sacrifice of

atonement that the celebration of the Mass reproduces, their faith in

the sacramental and hierarchical priesthood that Jesus Christ instituted.

Is it not paradoxical that these days everything is freely allowed, but that

one single freedom is restricted: that which wishes to be exercised along

the traditional paths, which is refused by those who still control many

levers of power, and which is so restricted by them that it is in fact rendered null,

all in the name of a “spirit” of a Council that sought to be, or was sought to be,

a “liberating” council?

***

(1) “Nel 1982 neanche l’alleanza Ratzinger-Casaroli riuscì a sdoganare la Messa tridentina,”

Il Foglio, 19 March 2006.

(2) Besides Cardinal Ratzinger as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, there were: Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio, Prefect of the Congregation of Bishops; Cardinal William W. Baum, Archbishop of Washington; Cardinal Agostino Casaroli, Secretary of State; Cardinal Silvio Oddi, Prefect of the Congregation of the Clergy; Archbishop Giuseppe Casoria, then pro-Prefect of the Congregation of Sacraments and Divine Worship.

(3) Bishop Müller, new Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, while bishop of Regensburg, undertook the publication of the complete works of Joseph Ratzinger in 16 volumes. In the volumes published so far, there is no hint of this 13 July 1988 speech, which could have been placed in volume 7 on the teaching of Vatican II, its formulation and its interpretation, or again in volume 11 on the theology of the liturgy. To be continued . . . .

(4) Abbé Claude Barthe, "Rome/Fraternité Saint-Pie X : où en sommes-nous ?” L’Homme nouveau, 5 January 2013.

No comments:

Post a Comment